Title: The Origin of the Milky Way

Author: Tintoretto

Date: 1575

Style: Mannerism

Genre: mythological painting

Media: oil, canvas

Location: National Gallery, London, UK

Title: The Origin of the Milky Way

Author: Tintoretto

Date: 1575

Style: Mannerism

Genre: mythological painting

Media: oil, canvas

Location: National Gallery, London, UK

For more than 200 years, Brandenburg Gate has served as the national icon for an evolving German identity. In the 1730s, King Frederick William I issued orders for the Prussian capital of Berlin to be fully enclosed by a wall. Built not to defend the city, but to tax people as they traveled in and out of town, the Customs Wall was intended to reduce the power of the estates general (the clergy, wealthy merchants, and lesser nobles) by transferring their capital to the crown who spent it on a large professional army to expand the kingdom.

Fifty years later, King Frederick William II decided that the Customs Wall, while useful, was not an aesthetically pleasing way to enter the city. He wanted a much grander entrance befitting royalty but that would also serve to impress and intimidate visitors. Of the eighteen small gates originally set into the wall, only one led to the royal palace on the outskirts of Berlin and to the city of Brandenburg beyond. It was at this site that the monument known today as the Brandenburg Gate would be constructed.

Completed in 1791 by architect Carl Gotthard Langhans and sculptor Johann Gottfried Schadow, Brandenburg Gate was a Neoclassical masterpiece that immediately became one of the most recognizable structure in Berlin. Its imagery combined representations of peace with classical allusions to famous victories, suggesting that Prussia’s peace rested on its successful military conquests under the leadership of its king.

In 1806, the city of Berlin was invaded by France. To celebrate his conquest, Napoleon used Brandenburg Gate for a triumphal procession before carrying the Gate’s bronze quadriga statue back to Paris as spoils of war. After eight years as a French satellite, Prussia rebelled against Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo. The Prussian army was able to seize the quadriga and return it to its rightful place. To mark this new victory, the goddess statue was supplemented with an Iron Cross, a military decoration first given to Prussian soldiers who fought in the Napoleonic Wars, and the Black Eagle, the primary element of the Coat of Arms of the Kingdom of Prussia. These two additions suggest that the symbolism of Brandenburg Gate had shifted slightly, focusing less on the power of the Prussian king and more on the power of the Prussian military.

This victory over France and the increased national pride that followed was exaggerated over the course of the next century, eventually becoming a devastating nationalism that led to the rise of Adolph Hitler and his Fascist government in 1933. Hung with the red flags of the Nazi party, Brandenburg Gate became a party symbol. The Athenian iconography of the relief sculptures of the battle between the Lapiths and the Centaurs, representing the victory of civilized men over barbaric and nonhuman creatures, would have appealed to Nazi ideals.

Berlin was bombarded in the final days of World War II and Brandenburg Gate, the city’s symbol of victory, national pride, and the Nazi party, was a frequent target. Although it was highly damaged, the Gate survived the war and became a witness to a new era of history. Because of its central location in the city, Brandenburg Gate was used to mark the boundary between Communist East Berlin and the Federal Republic of West Berlin. Walled off from both sides with concrete and barbed wire, the Gate was not accessible to the public for nearly thirty years.

However, with the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Brandenburg Gate was integrated back into the reunited country. To ensure its new place as a symbol of unification, West Germany’s Chancellor Helmut Kohl, walked through Brandenburg Gate to meet East Germany’s Prime Minister, Hans Modrow on the other side. Although the Gate today represents a united Germany, its solid presence also acts as a reminder of this once divided nation.

Today the Brandenburg Gate is a key symbol of modern Berlin and visited by tourists daily. Still dominating the Pariser Platz after more than two centuries, the Gate remains the visual embodiment of German identity.

[SOURCE:cyark.org]

Title: Romulus and Remus

Author: Peter Paul Rubens

Year: 1615

Genre: mythological painting

Medium: oil on canvas

Location: Capitoline Museums – Rome , Italy

Title: The artist dreaming in his workshop

Author: Emile-Louis Foubert

Medium: oil on canvas

Year: 1886

The Pantheon was built as a Roman temple and completed by the emperor Hadrian around 126 A.D. The name “Pantheon” comes from the Greek, meaning “honor all Gods” and this exactly was its purpose. As with most of the ancient monuments in Rome also the Pantheon has more than one story to tell. Most historians believe that Emperor Augustus’ right hand, Agrippa, built the first Pantheon in 27 BC, but the building burned down in the great fire of 80 AD and was rebuilt by Emperor Domitian. But again the temple was struck by lightning and burned down once more in 110 AD. The Pantheon as we know it today was finally built in 120 AD by Emperor Hadrian. In 609 A.D the Pantheon was transformed into a church which might be the reason that it was saved from being destroyed during the Middle Ages. And yes, there are Sunday Masses for everyone to join until today. Truly fascinating are the 16 massive Corinthian columns (12m/39 ft tall) at the entry and the giant dome with its hole in the top, also called “The eye of the Pantheon”, the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world and considered a great architectural achievement. The first king of unified Italy, Vittorio Emmanuelle II is buried in the Pantheon and so is his son, King Umberto I as well as the famous Renaissance painter Raphael.

[SOURCE:www.wostphoto.com/rome-pantheon]

Title: Hercules Removes Cerberus from the Gates of Hell

Author: Johann Köler

Year: 1855

Medium: oil on canvas

Location: Art Museum of Estonia

Title: Diana and Apollo Killing Niobe’s Children

Author: Jacques-Louis David

Year: 1772

Style: Neoclassicism

Media: oil, canvas

Location: Dallas Museum of Art

Title: Archduke Leopold Wilhelm and the artist in the archducal picture gallery in Brussels

Author: David Teniers the Younger

Year: 1653

Genre: interior view

Medium: oil on canvas

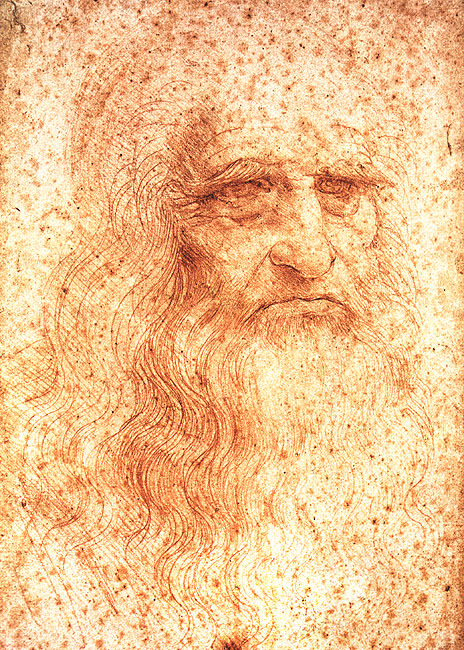

( This self portait was painted in 1512 using red chalk, when Leonardo da Vinci was 50 and living in France )

[ Biography ]

Leonardo was born on April 15, 1452, in the town of Vinci. His father was Ser Piero, a notary; his mother, Caterina, came of a peasant family. They were not married. The boy’s uncle Francesco may have had more of a hand in his upbringing than by either of his parents. When Leonardo was about 15, he moved to the nearby city of Florence and became an apprentice to the artist Andrea del Verrocchio. He was already a promising talent. While at the studio, he aided his master with his Baptism of Christ, and eventually painted his own Annunciation. Around the age of 30, Leonardo began his own practice, starting work on the Adoration of the Magi; however, he soon abandoned it and moved to Milan in 1482.

In Milan, Leonardo sought and gained the patronage of Ludovico Sforza, and soon began work on the painting Virgin of the Rocks. After some years, he began work on a giant bronze horse, a monument to Sforza’s father. Leonardo’s design is grand, but the statue was never completed. Meanwhile, he was keeping scrupulous notebooks on a number of studies, including artistic drawings but also depictions of scientific subjects ranging from anatomy to hydraulics. In 1490, he took a young boy, Salai, into his household, and in 1493 a woman named Caterina (most likely his mother) also came to live with him; she died a few years later. Around 1495, Leonardo began his painting The Last Supper, which achieved immense success but began to deteriorate physically almost immediately upon completion. Around this same time, Fra Luca Pacioli, the famous mathematician, moved to Milan, befriended Leonardo, and taught him higher math. In 1499, when the French conquered Lombard and Milan, the two left the city together, heading for Mantua.

In 1500, Leonardo arrived in Florence, where he painted the Virgin and Child with Saint Anne. He was very interested in mathematics at this time. In 1502, he went to work as chief military engineer to Cesare Borgia, and also became acquainted with Niccolo Machiavelli. After a year he returned to Florence, where he contributed to the huge engineering project of diverting the course of the River Arno, and also painted a giant war mural, the Battle of Anghiari, which was never completed, largely due to problems with the paints. In 1505 Leonardo probably made his first sketches for the Mona Lisa, but it is not known when he completed the painting.

In 1506, Leonardo traveled to Milan at the summons of Charles d’Amboise, the French governor. He became court painter and engineer to Louis XII and worked on a second version of the Virgin of the Rocks. In 1507, he returned to Florence to engage in a legal battle against his brothers for their uncle Francesco’s inheritance. In this same year, he took the young aristocratic Melzi as an assistant, and for the rest of the decade he intensified his studies of anatomy and hydraulics. In 1513, he moved to Rome, where Leo X reigned as pope. There, he worked on mirrors, and probably the above self- portrait. In 1516, he left Italy for France, joining King Francis I in Amboise, whom he served as a wise philosopher for three years before his death in 1519.

[SOURCE: sparknotes.com]

Title: Pallas and Centaur

Author: Sandro Botticelli

Year: 1482

Style: Renaissance

Genre: mythological painting

Location: Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy